Some time ago I discovered the most amazing miniature bronze dinosaur skeletons listed on the Maxilla & Mandible website. M&M is like something out of a Harry Potter movie—an exotic shop tucked away in the heart of New York crammed full of fantastical items for the naturalist (skeletons, assorted bones, skulls, insects, shells etc etc). I did mail-order some of their smaller skulls when I lived in the USA and they were excellent! A few years ago I finally got to visit the shop, which is located close to the American Museum of Natural History. Wonderful! After a bit of research I found the gorgeous miniature bronzes they list for sale were the work of Nelson Maniscalco.

Because they're bronze, they are structurally robust and Nelson's work has a wonderful sense of movement and dynamism—the skeletons seem to float in mid air. These are no ordinary skeleton models—each is beautifully detailed and accurate, truly a museum exhibit in miniature. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

About Nelson Maniscalco

With a combined mold making and casting experience of over

35 years, fossil hunters Nelson Maniscalco and Marty Shemella are

highly skilled in reproducing detailed fossils and skeletons. They

continue to make molds and castings for museums around the world and

more than a few of their bronze dinosaur skeleton castings reside in the

collections of such notable celebrities as movie mogul Steven Speilberg

and horror author Steven King. Both Maniscaclo and Shemella are

currently part of the teaching staff at Cedar Crest College in

Allentown, Pennsylvania, which boasts a well appointed and growing

foundry where a variety of metals are cast including bronze, copper,

iron, gold, silver and platinum.

“As a lifelong student and teacher of fine arts, I might not be the likeliest suspect to create dinosaur sculptures and participate in dinosaur digs. However, the progression from fine artist to dinosaur sculptor and amateur paleontologist developed as I came to appreciate more and more the structural beauty of the earth's earliest rulers. It is only natural that as my fascination with the anatomical forms of these magnificent dinosaurs grew, it would find expression in my creative works, such as my dinosaur sculptures for Maxilla & Mandible”

—Nelson Maniscalco

from Dino Press Vol. 5, 2001

Recent Sculptures

Gallery

"Velociraptor Battle"

"Death Struggle"

Zuniceratops & Deinonychus

"Styracosaurus"

"Combat—Allosaurus life-and-death struggle"

"Deinoychus Alpha Males"

"Pterosaurs"

"Smilodon Battle"

"T. rex"

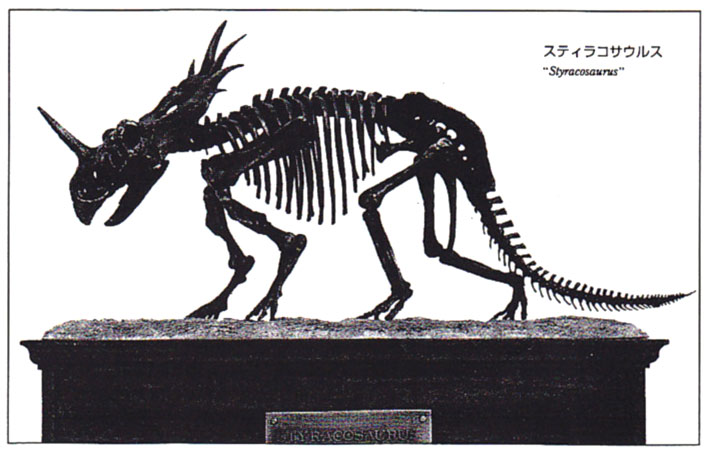

"Styracosaurus"

Dino Press Article

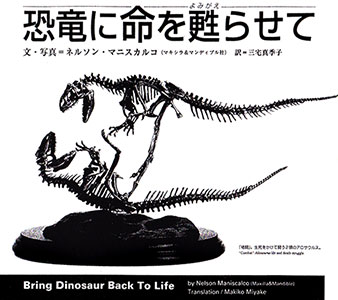

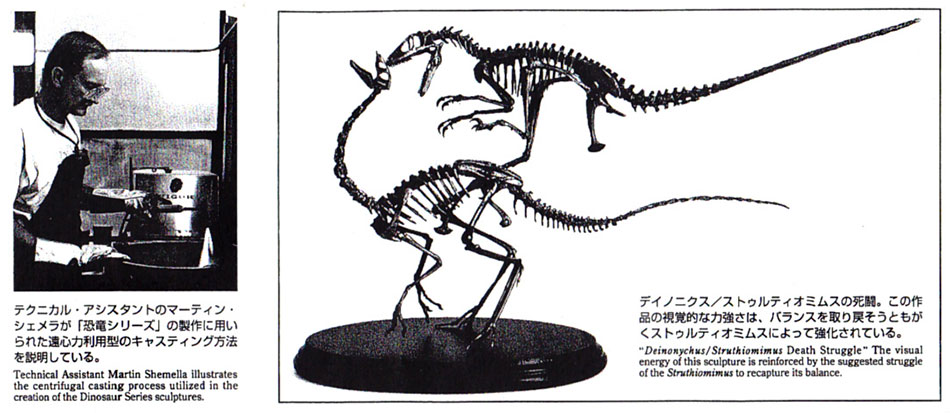

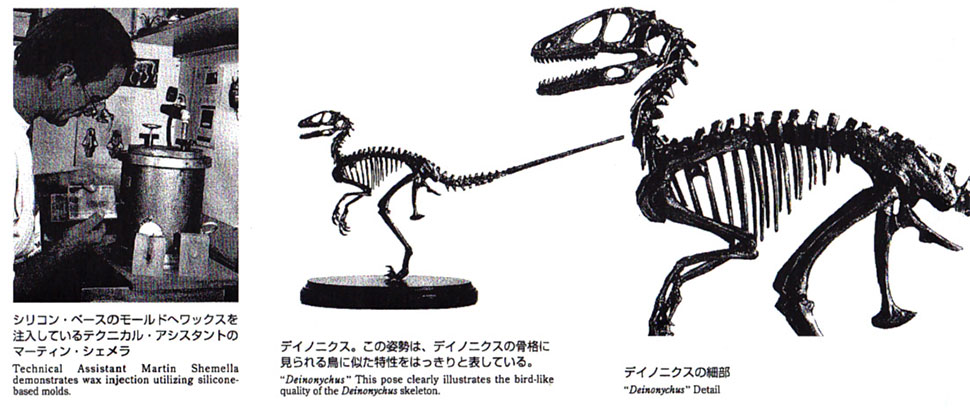

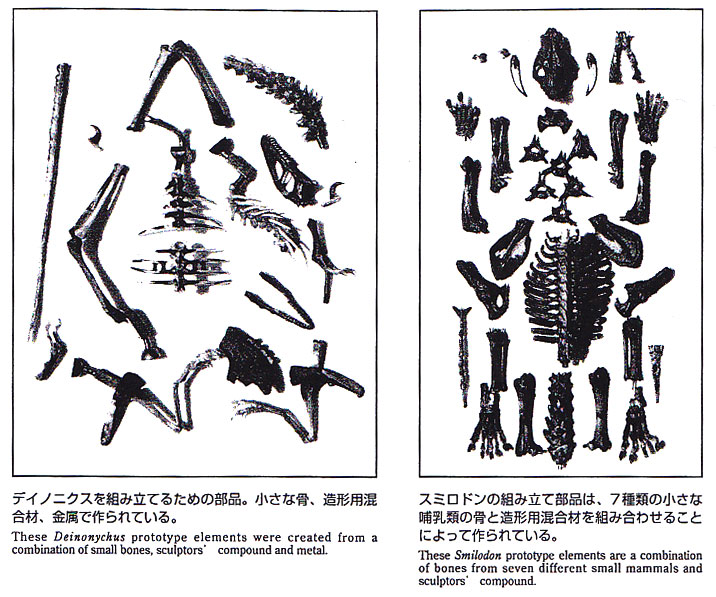

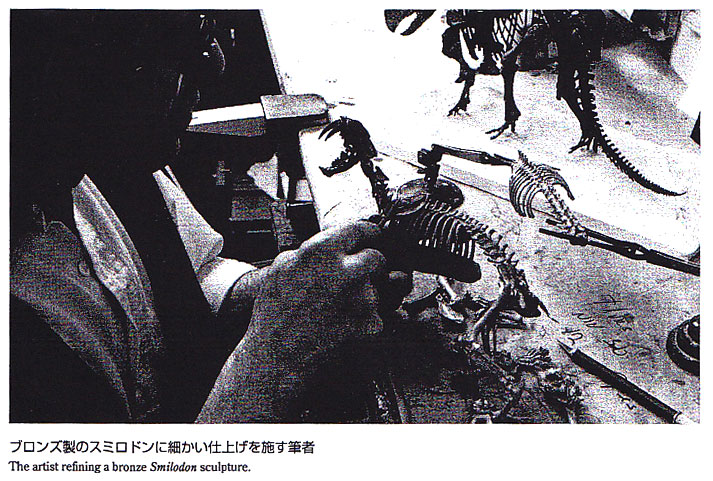

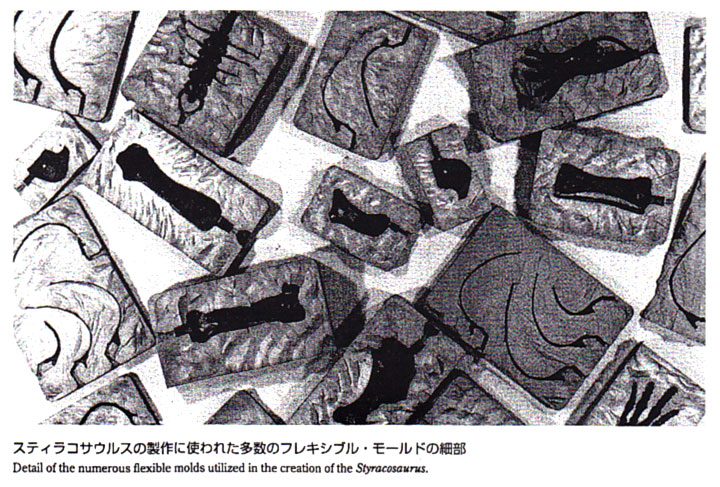

The following images are from an article published in the short-lived but highly regarded Japanese magazine Dino Press in 2001. A black and white photocopy was kindly sent to me by Horst Bruckmann, which I scanned. Image quality is not great but even so, it's clear that Nelson made a wide range of amazing bronze miniatures and went to great lengths to achieve scientific accuracy with dynamic artistic flair. The results are fabulous!

UPDATE

Nelson Maniscalco has since kindly sent me an English translation of the Dino Press article, find it below.

Dino Press Article English Translation

Bringing Dinosaurs Back To Life

by Nelson Maniscalco

p.92-97

As a lifelong student and teacher of fine arts, I might not be the likeliest suspect to create dinosaur sculptures and participate in dinosaur digs. However, the progression from fine artist to dinosaur sculptor and amateur paleontologist developed as I came to appreciate more and more the structural beauty of the earth's earliest rulers. It is only natural that as my fascination with the anatomical forms of these magnificent dinosaurs grew, it would find expression in my creative works, such as my dinosaur sculptures for Maxilla & Mandible.

Like so many others of my generation, my interest in prehistoric creatures began when, as a child, I first witnessed Godzilla emerge from the waters of Tokyo on a small black and white television in my Grandmother's living room. I aggressively pursued this new interest by paying regular visits to all the major natural history museums of Pennsylvania and New York. It was in those massive halls that I first encountered skeletal reconstructions of the great giants that dominated Earth's landscape for millions of years. Towering dinosaurs; flying reptiles the size of small aircraft; giant sloths; pachyderms with long, twisting tusks; and tigers with 15-inch sabers all were reborn into the 20th century, as they appeared to walk through the halls of these great museums. Although stripped of their flesh, these bone machines were magical in the power of their scale, the elegance of their forms, the clarity of their function and the dynamic energy they possessed.

The more I saw, the more my curiosity grew. In those early years, I became passionate about the history of life and the aesthetics of bones. I would sketch these images repeatedly in an attempt to infuse them with new life on the page. I began collecting the bones of extant animals from the side of roads, railroad beds and in the neighborhood fields. I would study, draw and articulate them whenever possible. Over the years, my use of skeleton images became increasingly symbolic. By the time I left graduate school and emerged as a professional artist, bone images were at the center of my sculptures.

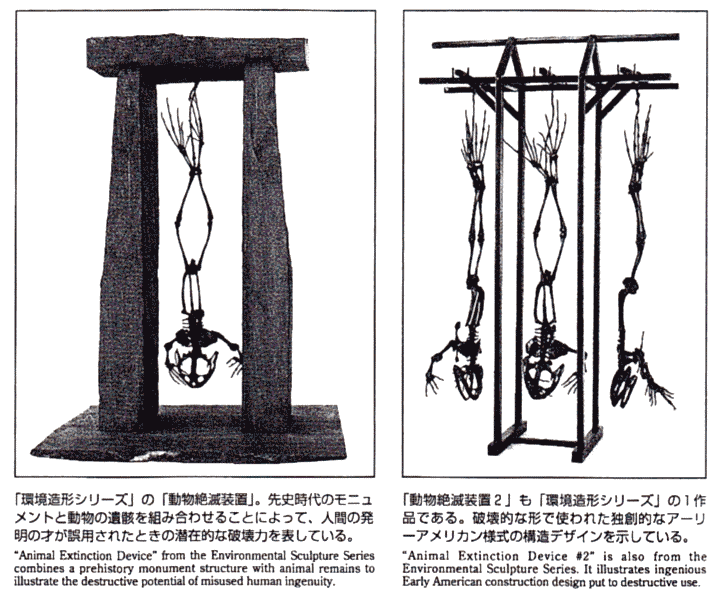

My work through the 80s and early 90s focused on the destruction potential of unchecked human activity on the natural environment. These images were intended to reflect upon the fragile nature of life and the possibility of forced extinction. often created bronze bullfrog and brown bat skeletal interpretations to represent animal life and death. These skeletal interpretations were then incorporated into scaled-down architectural structures reminiscent of various periods in human history. Combined with skeletal elements, these were meant to portray the uniquely human potential for innovation and creation, and consequently, the destruction that would ensue for the environment and other life forms if these powers were abused.

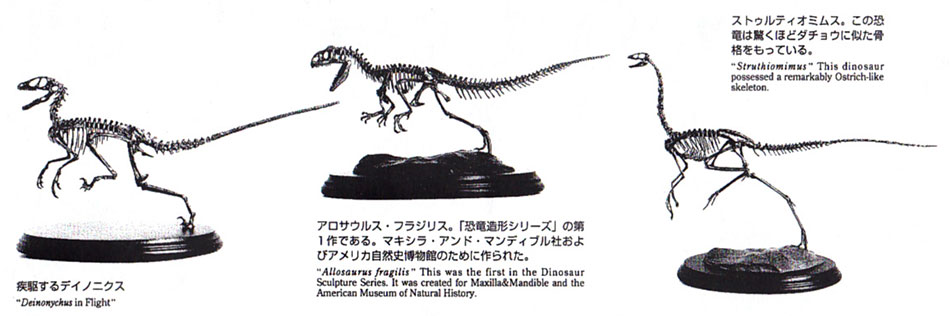

During this period, I was showing works from this Environmental Sculpture Series exclusively in art galleries and museum exhibitions. In the mid-90s, this sculpture series attracted the attention of Maxilla & Mandible, Ltd. of New York City. My sculptures were congruous with their focus on the relationship between art and science, and they began representing me in 1994. Later that year, as the American Museum of Natural History in New York City was preparing to close its dinosaur halls for renovation and redesign, Maxilla & Mandible proposed a commemorative bronze skeletal dinosaur series for display and sale at the museum. The museum accepted the proposal, and I began the process of shifting from extant skeletal animal forms to the extinct. The plan was to create small-scaled bronze interpretations of the magnificent Allosaurus/Barosaurus attack display in the Roosevelt Hall of the museum. What I initially thought would be a subtle shift in concept and technique proved to be one of many challenges.

The foremost challenge centered on understanding the difference in artistic purpose between the use of skeletal structures in the Environment Sculpture Series and the Dinosaur Series. Clearly, in the Environmental Sculpture Series, I used extant animal skeletal structures as symbols or metaphors of animal life and death in highly conceptual pieces. This allowed, and at times required, that I distort, exaggerate and evolve the skeletal structures to support the ideas and visual dynamics of the pieces. The scientific integrity of the skeletal structures was without purpose and by necessity, expendable. Their intent was not to communicate scientific knowledge or theory, but to raise social consciousness about pressing environmental issues of the day. As I shifted venues from the art gallery to natural history museums, my responsibilities to scientific integrity and accuracy needed to be adjusted accordingly. My new purpose in the Dinosaur Sculpture Series was to create images that resurrected a moment in the lives of creatures that lived more than 65,000,000 years ago, capturing the passion, energy, and violence of the times. Scientific accuracy was now crucial. It was essential that the bone designs, the skeletons' movement potential and the gestures of the poses accurately communicate contemporary scientific thinking.

Before even considering touching a piece of sculptor's wax or bronze, I would need to assemble as much information as possible about dinosaur anatomy, movement, behavior, and history. While developing the Environmental Sculpture Series, I came to understand animal movement by drawing from direct observations of nature, comparative anatomy texts, and the works of great scientifically-based artists like Cuvier, Stubbs, and Muybridge. Understanding dinosaur movement was much more difficult. In many cases, our understanding of dinosaur movement potential is based upon information gathered from fragmentary specimens, assumptions about musculature, and unique bone designs that have long been extinct. I knew the search for reliable information would be difficult. Fortunately, as a member of the Maxilla & Mandible family and a Professor of Art at Cedar Crest College, I had access to some of the best scientific minds and libraries of our times. These sources provided me with both current papers and historical writings on dinosaur anatomy, movement and behavior. Having amassed a strong information base, I was ready to move on to the next challenge.

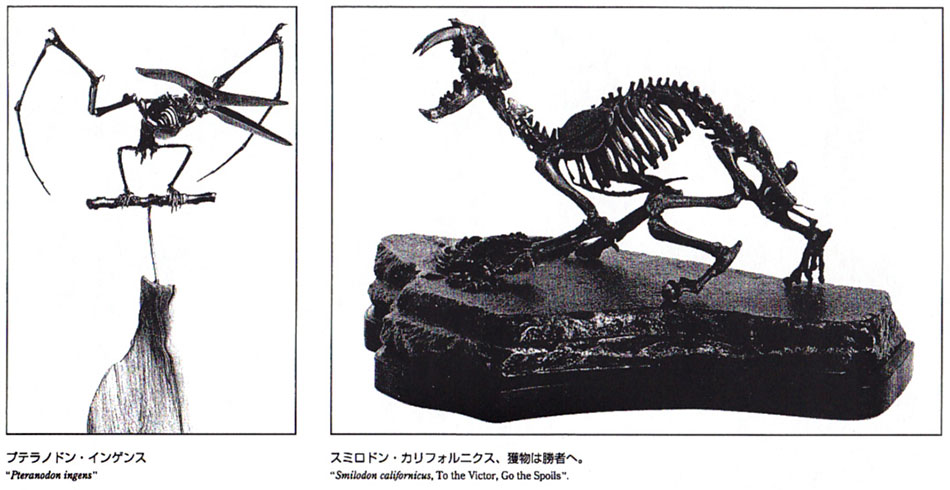

These skeletal systems had to possess dynamic, lifelike gestures and exhibit an accurate range of motion, while retaining the ability to be assembled in a variety of different poses. Essentially, I needed to create an elaborate puzzle system with a high level of flexibility and strength. For this reason, the skeleton could not be modeled as a complete unit. Using the Styracosaurus as an example, if I were to present the Styracosaurus in a full charging position in one sculpture and a dramatic twisting pose in another, I could not rely on simply twisting or bending the complete spinal column. In this case, the integrity between individual vertebra would be compromised. There would need to be fluid movement between the articular surfaces of each individual vertebra. The same consideration would need to be given to every joint of the body to accomplish a full range of accurate movement.

A dynamic sense of living energy had to be accomplished solely through the relationship of the bones and the positions of the poses. If we reflect back to the fully fleshed bronze creatures of Barye or Rodin, we see that they were able to create a powerful sense of visual tension by exaggerating the textural surfaces, and stretching or compressing the flesh, muscles and tendons of their creatures. The dynamic tensions built across their surfaces were consistent with the powerful painterly surfaces of the abstract expressionist paintings of the last century. Combined with dramatic poses, their creatures were full of life and passion.

Without the advantages of the great size and mass of the actual museum specimen, the taut and twisting flesh of the complete animal, or the textural interpretations of the surfaces, I would need to rely completely upon the poses and flexibility of the creatures' joint systems to create this high level of visual energy. For this reason, I chose to individually model, mold and cast each bone that would require appreciable movement, and assemble each sculpture, bone by bone, to accomplish my poses. Returning to the Styracosaurus example, each of these sculptures is the result of assembling 59 separate bone parts.

The next consideration was to create joints capable of full and natural movement. I decided to work directly with real bones, resizing and sculpting each bone to transform it from the bone of an extant animal to that of an animal extinct for millions of years. The first step involved assembling a full complement of small, extant animal bones that were similar in design and function to that of the dinosaur I was creating. In the Deinonychus sculpture, I utilized bones from a variety of reptiles, mink, rat, bat, bird, snake, and finally, fish for teeth. I diced, spliced and sculpted each bone, paying careful attention not to compromise the joint systems. The result of that exercise was a complete assortment of miniature dinosaur bones that, in theory, would articulate into a complete creature with a full range of movement, accurate design and true proportions. I then articulated these prototype bones and determined that the skeletal system would work as a complete animal.

The next step was to disassemble the skeleton and begin researching molding and casting processes. It became apparent that traditional bronze pour-casting and molding techniques would be ineffective in reproducing these bone units. They were much too delicate, intricate and complex. Also, gates and risers, critical to the bronze pour-casting process, would seriously compromise the forms and joint surfaces. Because each of these bone units was like a delicate piece of jewelry, I began experimenting with jewelry casting and jewelry-based, limited- production processes. I tested a number of silicones, urethane and latex flexible mold materials to determine which compounds offered properties most consistent with my needs. I settled on three different compounds for three different bone types. I then used these molds in combination with a jeweler's airdriven wax injection system to create wax reproductions of the individual bone prototypes.

With the reusable molding process resolved, I began experimenting with various casting techniques. Again, the jewelrymaking industry held the solution. I found that jewelry-scale centrifugal casting and vacuum-assist casting provided me with the required force and adjustments to accommodate a wide range of delicate and complex bone designs. I executed my first casting run in silicone bronze, and experienced my first major disappointment. Although silicone bronze has ideal properties for most sculptures, and has always served me well in the past, it did not possess the strength and durability for the forms and poses that I required. If you look to the Deinonychus/Struthiomimus Attack sculpture, you will note that both animals are supported in space by two small pins. A majority of the mass of both animals is thrust well forward of the center of gravity, essential to the violent energy of the piece. Although silicone bronze was rigid enough to support the weight without sagging, it was too brittle and prone to cracking. Silicone bronze was also a bit too sluggish in the cast, resulting in about a 50% failure rate. I performed a number of experiments with slight adjustments to the metal until I produced an alloy with the precise properties needed. My casting success rate is now above 90% and the sculptures are remarkably durable.

Over the course

of my seven-year journey into the past, I learned a tremendous amount about the

history of life and the small scale bronze casting process. The most

significant thing I came to understand was the profoundly important contributions

that dinosaur artists make to scientific study and to our understanding of this

unique group of animals. Dinosaur artists are often the first to translate new

scientific theories into physical or visual forms. They test new ideas about

body design, balance, movement and locomotion. They speculate about animal

coloring and behavior. They take ideas and possibilities and they give them

life.

What began as a project to create a small-scale interpretation of the Allosaurus/Barosaurus attack scene has grown to include six dinosaurs, a Smilodon, and a number of extant animals. By varying their positions and combining different animals in life-and-death struggles, I have expanded this series to more than 70 different sculptures. Triceratops and Protoceratops will soon leave my workbench to join the series. The next creature to be born in my studio will be my interpretation of a potentially new genus and species of Pachycephalosaurid from the celebrated "Sue" site. I was fortunate to be a part of that discovery. Once the bones are freed from their jackets and available for study, I will bring this animal back to life through the magic of bronze sculpture.