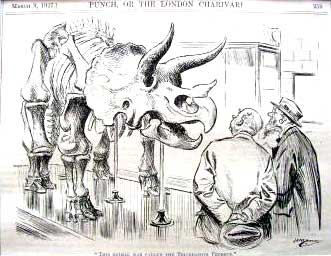

"Ceratopsians were rhinosceros-like animals. But there is a danger in that analogy. ... It is an easy subliminal error to fall into, succumbing to the pull of the present. ... The image of the dinosaur has been refurbished and the sleek hyperkinetic saurians of today's movies are aesthetically appealing, irrespective of whether or not they are accurate."

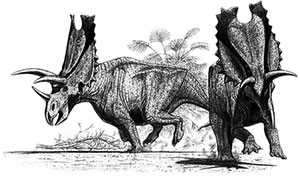

"What about Triceratops and its ceratopsid friends? Artists have striven to rescue ceratopsids from the ignomy of the past. Ceratopsids prance and dance on canvas, sleek as greyhounds, lithe as ballerinas."

In the museums they are not doing so well. Their hind legs are fine, underneath the body as they should be. But there is a problem with ceratopsid posture, and it is centered on the front legs. They sprawl. When Marsh first reconstructed Triceratops, on paper, it came out with erect columnar limbs, front and back. But when skeletal mounts began to be erected, first in Washington, then in New York and Ottawa, the front limbs just didn't work out the way they were expected. To be blunt, it is impossible to mount the forelimbs of ceratopsids with the joints articulated, the limbs erect, and the elbows rotated underneath the body. They simply don't go together that way..."

"The limits are imposed by the skeleton itself, especially the humerus. The bulbous head of the ceratopsian humerus is off-centrer, projecting onto the back surface of the shaft. This structure makes it virtually impossible to mount the humerus vertically. In addition, the upper end of the humerus is rather rectangular, with the bulbous head in the middle; the farther the humerus is drawn upright, the greater trhe tendancy of the inside corner (lesser tubercle) to puncture the ribs."

Sprawling front legs are not so energy efficient, especially for such a big animal. It therefore demands a very good evolutionary premise.

To me, the clue is in the skulls; their huge size and amazing ornamentation is a defining characteristic. Another clue is the scapula and humerus which were certainly engineered for huge supporting muscles. Of course a sprawling posture keeps the head down in an eating position, but I believe they did more than sprawl; I think they really did do pushups—and aggressively at that! I can easily imagine them bouncing on their front legs and thrusting their fantastic horned cranium up and back to show off their massive and imposing heads. They had the musculature for it. Such a display would certainly have intimidated predators and rivals. It no doubt would impress the ladies too. What an amazing sight that would be!